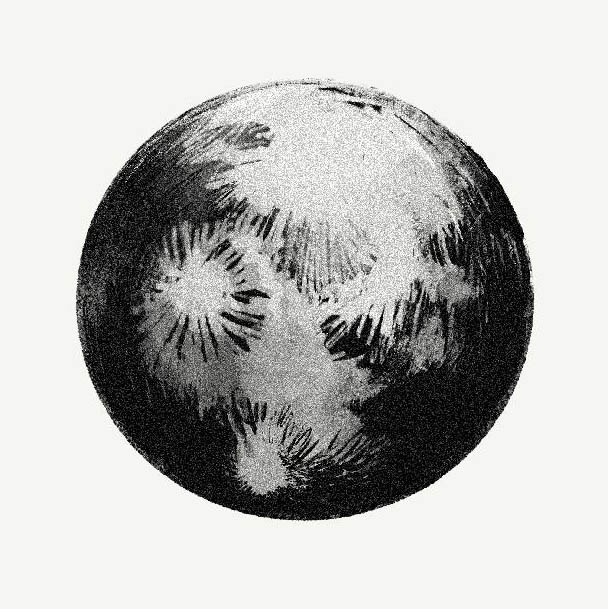

"In every dream, whether you are conscious of it while you are dreaming or not, there is some kind of natural phenomenon present. Either it's night and there is a night sky, with or without stars; the sun is shining in the day or it's cloudy; there is a feeling of wind present or not. There is always some kind of natural phenomenon and that is because you cannot dream without the natural phenomenon; it is the nature of things, out of which the dream arises."

Bartholomew, Taos, NM

I.

From ancient times people have looked to dreams for visions of the divine realms above, and/or the demonic underworld below. But in our time, with our society's pressing environmental troubles, we need to ask a different question of our dreams: what do dreams tell us of this world, the natural world between Heaven and Hades? Can dreams help us heal our wounded, suffering Earth?

Yes they can. In my opinion, we need to listen more carefully to dreamers from non-western cultures, who have always believed that dreams do speak directly to important communal and environmental issues. As recent anthropological studies have shown, indigenous peoples from central and South America, Africa, and Oceania firmly believe that dreams bring forth meanings that are extremely valuable for the community's well-being. They believe that dreams comment on the community's affairs, point to longignored social problems, and offer visions of communal reform, renewal and hope.

We need to realize that the narrow focus on personal, individual meanings is a strictly western view of dreams. Dreams have many, many different dimensions of meaning. Which of those dimensions we discover in our dreams is always determined by the questions we ask of them. If we ask questions about our personal conflicts, that's what we will learn about; but, if we ask questions about the crises facing our culture, we will find that our dreams have much to say about that, also.

Even if we grant that dreams do tell us something about social matters, can they really help us with a problem as massive and intractable as our environmental crisis? The threats of global warming, species extinction, and mounting toxic wastes are tied up with terribly complex political and economic issues; dreamwork, it would seem, is a fly-swatter in comparison to such elephant-sized problems.

Here, we need to listen to what environmentalists themselves say we need to overcome these problems. Most environmentalist action involves lobbying politicians to change laws, protesting against corporate polluters, and trying to develop cleaner, safe technologies. Yet many leading environmentalists admit that these efforts are not enough; they say that we need a deeper, more fundamental change in people's values and attitudes regarding Nature.

Bill McKibben, author of The End of Nature, says "We must invent nothing less than a new and humbler attitude toward the rest of creation. And we must do it quickly." Petra Kelly, founder of the Green party in West Germany, states "Saving life on Earth requires not only a new way of thinking, but also a new way of feeling. We must work with our minds and with our hearts." And Peter Bahouth, executive director of Greenpeace in the U.S., insists that "the way to change the assumptions that are destroying the earth is to combine personal transformation with a hard-headed, practical campaign of coalition building, demonstrating and organizing."1

These environmentalists are all saying, in different ways, the same basic thing: we need, more than anything else, a deep transformation in the basic values and attitudes that guide our society's treatment of the Earth.

My claim is that dreamwork can contribute to this task. Dreams may not help us create new environmental laws or technologies. But, dreams can promote exactly the sort of transformation of moral and spiritual values that environmentalists say we desperately need. Throughout history dreams have been a potent source of new visions, energies, and ideals that have helped people overcome seemingly insoluble problems. Today's dreamworkers have a great opportunity: to help bring the wisdom of dreams to bear on our community's environmental problems.

II.

Little practical research has been done on the specific question of how dreams can promote greater environmental awareness. However, I have an example that might help to indicate the potential dreams have in this regard.

Sam LaBudde is a marine biologist with the Earth Island Institute in San Francisco. In 1987 he engaged in a dangerous environmental spy mission: he anonymously took on a job as a mechanic on the Maria Luisa, a Panamanian fishing boat hunting the Pacific for yellowfin tuna. Schools of tuna are frequently accompanied in the ocean by dolphins, and fishermen had long been accused of recklessly slaughtering the dolphins in the process of catching tuna. However, environmentalists had no hard evidence to use against the tuna fishing industry. LaBudde brought a video camera onto the ship, and whenever the crew hauled up its nets, he casually videotaped the ghastly proceedings: scores of dolphins tangled in the mesh, beaks cut, fins broken, drowned in their struggles. Even though he knew the crew would beat or kill him if they discovered his true purpose on the ship, LaBudde managed to collect extensive video footage. When he brought his films back to the U.S., they caused a sensation-they were shown on national newscasts and at congressional hearings, and they helped ignite a public outcry over the tuna fishing industry's environmental practices.

Months after his voyage on the Maria Luisa, LaBudde suffered a recurrent dream: there were "injured dolphins speaking in cryptic tongues"; the dolphins were "bandaged, crutch-ridden, swathed in all the symbols one would expect from a participant or victim of a war." LaBudde says he feels the dreams reflected "stuff I had to bury on the ship because my desire to speak out or do something about the dolphin kills had to be suppressed."

More recently, LaBudde has dreamed of "annihilating representatives of bureaucratic corporate America"; these dreams, he believes, "are a way of purging that which I fail to deal with during my waking states ... [They're] an outlet that helps me resist the urge to become a felon (for the Earth, of course)."

LaBudde's dreams and his understandings of them provide us with some valuable insights into the question of how dreams can contribute to environmental awareness and action. First, his dreams are about environmental problems; the dreams probably have personal, intrapsychic meanings too, but they are certainly speaking directly to our society's environmental crisis. Second, LaBudde's dreams present powerful, moving images of that crisis. The wounded dolphins hobbling on crutches, struggling to communicate is a tragic, strikingly poignant image that haunts LaBudde long after his voyages; the. annihilation of corporate bureaucrats, by contrast, is a wish-fulfilling fantasy that seems to refresh him and clean out his aggressions.

These dreams prompt LaBudde to further environmental action. The dolphin dreams remind him of the dolphins' torment, spurring him to continue fighting on their behalf; the corporate bureaucrat dreams seem to show him that although it might be satisfying to blast these people out of existence, there may be less violent, more effective ways for him to protect the environment.2

People's dreams often bring forth striking natural images-raging storms, fantastic creatures and plants, cataclysmic earthquakes, mysterious caves, fiery volcanoes. Most western interpreters view such images as personal metaphors (e.g. dreaming of an earthquake might mean the dreamer's world is being "shaken up"). But we also need to appreciate how, in another dimension of meaning, these dream images speak to us about our relationship with Nature; they tell us (among other things) that Nature is powerful beyond our reckoning, full of beauty and wonder, and deserving of our respect.

Bill McKibben speaks of the need for a "new and humbler attitude toward the rest of creation" if we are to stop humankind's destruction of the natural world. It can be difficult to cultivate such an attitude in our waking lives where we so easily control and manipulate the environment. Our dreams, though, remind us of our true relationship to the Earth; we are but one species of creatures in the mysterious unfolding of life, an unfolding that can be incredibly joyous, humbling, and beautiful.

III.

What good is dreamwork for people who aren't already committed to environmentalist values? Can dreamwork promote a transformation of values and attitudes throughout our society regarding our treatment of the Earth?

I would respond by pointing to the most crucial, fundamental insight of the environmentalist movement, which is that all life is interconnected - as John Muir said, "when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe".3

Western society has long asserted that humans are separate from the Earth, and that we can use, exploit, and destroy the natural environment however we wish. Environmentalists have worked hard to overturn that view and to make people realize that we are integrally related to all of Nature. But their efforts have met strong resistance from stubborn, tenaciously held attitudes; environmentalists have found it very difficult to create the deep change in values and attitudes that are necessary for a more respectful relationship with the Earth.

Dreamwork can help promote that deep change. Dreams reveal to us how we are fundamentally relational beings. Anyone who explores their dreams learns to appreciate the complex web of relationships that create and sustain our lives. We learn through our dream experiences to appreciate the fundamentally relational nature of life - the countless ways in which our lives depend on healthy, balanced interactions with other people, other psychic forces within ourselves, and with the natural environment. Most importantly, dreamwork promotes this appreciation in a way that goes beyond mere intellectual agreement. Dreams often bring forth truths with great emotional power; thus we may think we understand the important relational quality of our lives, but our dreams can bring that truth home with a strong, primal, transformative force.

What, then, can dreamworkers do practically to cultivate this potential of dreams to change our values and attitudes toward Nature, to help heal our society's relationship with the Earth?

We can focus on images of Nature in dreams and, rather than reducing them to personal metaphors, can treat them as reflections on our treatment of the natural world. We can ask, what does it mean that I often dream of dark, dangerous forests? Does that affect my views of our society's use of natural resources? What about dreams of speeding around in fast cars - does that give any insights into our society's environmentally destructive obsession with automobiles? In dreams where birds, or fish, or rodents are prominent, might those animals be able to tell us something about the needs of Nature?

The crucial point is that we begin trying to ask such questions. Other cultures have always seen their dreams as speaking to their community's relations with Nature; they have regarded dreams as inner manifestations of the same cosmic forces that shape the natural world.4

Indeed, it's no coincidence that many Native American tribes have both a profound reverence for Nature and a profound respect for the communal wisdom of their dreams. Now, our culture needs to learn how to listen to this communal wisdom. We must begin to ask how our dreams can guide us in healing our relationship with the Earth.

Notes:

These quotes are taken from the article "How We Can Save It", Greenpeace Magazine (Jan / Feb 1990), vol. 15 #1 , pp. 4-8.

The information on LaBudde's experiences on the Maria Luisa comes from Kenneth Brower's article "The Destruction of Dolphins", in The Atlantic Monthly (July 1989), pp. 35-58, and from my personal correspondence with Brower. The quotations regarding the dreams themselves come from my personal correspondence with LaBudde.

John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra, as quoted in Roderick Nash's The Rights of Nature (Madison, WI; U of Wisconsin Press, 1989) p. 40.

This deeper connection between dreams and the environment - drea ms as an "inner wilderness", the environment as an "outer wilderness" - suggests that the dialogue could, and should, work in both directions. Not only can dreamwork contribute to environmental awareness and action; environmentalist insights can also contribute to dreamwork. In short, we also need to ask the question: What can healing the Earth tell us about dreams? While I don't have space in this essay to explore this other side of the dialogue, I would note the following ideas it suggests: that we not use dreams as "raw materials" to be exploited for our individual human desires and that we treat dreams with humility, respect, and reverence.