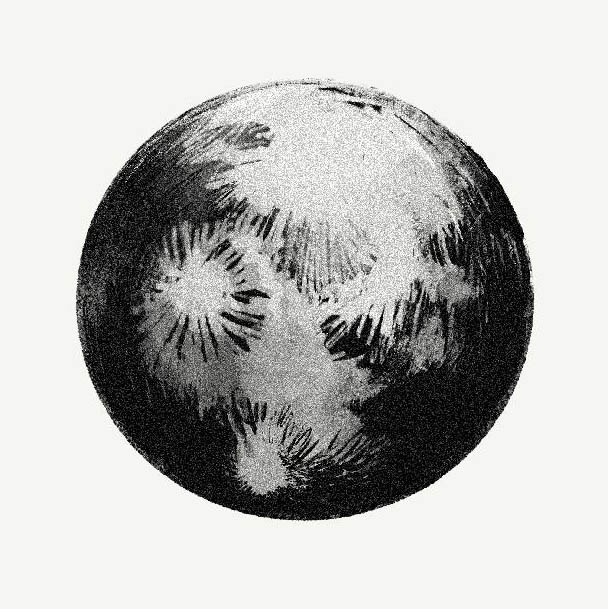

"There is a terrible storm. We struggle to the wheelhouse of the foundering ship, only to discover that it is filled with posturing lunatics who have left the wheel unattended. We are dismayed -all this time we had supposed that the brave captain and crew were struggling to save us, using all their skill and seafaring experience to keep the ship afloat..."

A nightmare indeed, but one which, like most nightmares, depicts our true circumstances with metaphoric accuracy.

The recent ABC television film, "The Day After", was sadly lacking in emotional or even technical realism. The only scream of agony was uttered by a woman in childbirth, and the fictionalized survivors in Lawrence, Kansas, bore about the same relation to the actual survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a Hallmark Christmas card to the agony of death on the cross. In the media debates which followed, the remarks of MacNamara and the rest made it disturbingly clear that the men who have been responsible for the formulation of weapons policy in the U.S. have,· despite their posturings, no idea about how to deal with the horrors those weapons have created.

But like all nightmares, the fear of nuclear war also places us more firmly in the true center of our lives and responsibilities. We must abandon the notion that we are being protected by our wiser and more informed leaders, and begin to look more seriously at what we must do to protect and save ourselves.

James Joyce said, even before the advent of the nuclear age, "History is a nightmare from which we are struggling to awake". Because the collective unconscious expresses itself in both the dreams of individuals and the larger, collective dramas of world history we share as a species, Joyce's formulation of the problem can be seen as psychologically accurate, as well as profoundly and poetically true.

The collective nightmare of nuclear menace comes to us in essentially the same fashion as individual nightmares -- it comes as the culmination of a series of somewhat less gripping and horrific "dreams" which we have been able to forget, ignore, and repress. One thing that can be said of all nightmares is that they take the horrific form they do in large measure to insure that they will be remembered upon awakening, so that their ultimately healing message will have a greater chance of being understood and acted upon.

All dreams come ultimately in the service of health and wholeness; and even the collective nightmare of nuclear menace is like the nightmares of individual dreamers in that it, too, has a positive, healing message to deliver. "What message?!?" you may well ask. In one sense, the answer to that question is so obvious as to be commonplace -WE ARE ONE. The bomb unites us all in an ultimately "practical" way that reveals the pettiness and pointlessness of all the criteria we habitually use to separate ourselves into seemingly irreconcilable camps of friends and foes. In this sense, the solution to the nuclear dilemma is obvious -- humankind is one family, and we must act accordingly. Or, to put it into traditional Christian terms --we must learn to love our enemies.

Indeed, this has always been the solution to our collective problems, proclaimed by all the great world religions and ethical philosophies over the millennia. However, in the present era, what was a rarified spiritual knowledge shared among only a few highly developed men and women has been turned into common knowledge by the horror of our increasingly sophisticated nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons technology.

Continued preparation for technological war that can only result in wiping out humanity (and all the other complex, warmblooded species besides) is as clear a metaphor of collective suicide as we have yet developed. If such preparation for self-destruction were undertaken by an individual, it would be easily recognizable as the hysterical desire to make self-destruction seem "inevitable" and "unavoidable", in preference to facing the necessity of growing and changing and letting go of outmoded ideas and self-images.

In dealing with the nightmare of nuclear menace, it appears we must adapt many of the same therapeutic strategies we would use in dealing with the dreams and self-destructive waking decisions of an hysterical potential suicide. We must gently and firmly raise to consciousness the repressed contents which are themselves the "cause" of the nightmares, as they struggle to express themselves in the homeostatic, "compensatory" activity of dreaming. We must also address with calm authority the hysterical wish to die rather than change. Most importantly, we must redouble our own efforts to come to grips with the increasing complexity of the truth as we encounter it ourselves, in our own lives -- giving up our own outmoded notions, and modeling the process of growth and change for our more frightened and repressed neighbors.

The appearance of imagery connected with the nuclear menace in the dreams of individuals regularly reveals a fear of change.

I worked recently with a woman who is employed, none too happily, as an administrator in a temporary "manpower" agency. She dreamed that her supervisor came to her with an advertising scheme focused on an image of the business world after the bomb, featuring a picture of executives in suits and ties laid out dead from nuclear radiation, in rows on desk tops. In the dream, the woman argued vehemently against this advertising scheme, speaking her mind more fully and forcefully than she would ever have allowed herself to do in waking life. However, when she worked with the dream, she realized (with the undeniable "aha!" that is the only reliable touchstone of dream work) that at one level the dream depicted her strong but unadmitted desire to quit her job and become more autonomous and independent.

At this level, the "aftermath of the bomb" was an image of her fear that if she were to act on her repressed desires to speak her mind and express her feelings more freely, perhaps even quitting her job and becoming self-employed, her "world" would become as "barren and inhospitable" as the world after the bomb.

And yet, at another level, the dream clearly depicted that part of her life which is already "barren and dead," despite the seeming economic security provided by her job. In this sense, the message of the image of nuclear holocaust is the same at the level of this individual dream as it is at the level of the collective: "It is time to grow and change!"

The image of the world devastated after a nuclear holocaust points to changes in individual and collective social relations that we must accomplish if we are to survive. We must make changes in our lives and habitual ways of acting and relating that are as radical and complete as the changes the nuclear holocaust would bring.

Such changes appear to be inevitable. Either we will bring them about through the suicidal self-deception of nuclear "accident" and war, or we will bring them about consciously and voluntarily in order to save ourselves from that ugly fate. Time and again, work with individual dreams of "the world after the bomb has fallen" reveals that image as metaphoric of the deep need to sweep away the restrictive and self-deceptive social roles and relations with which we paralyse our lives, and to build our lives anew.

At a collective level, the nightmare of nuclear menace reveals once again the ancient truth that death in dreams is always associated at a deep level with the growth and transformation of personality and character.

Although it is still too soon to say with certainty, I strongly suspect on the basis of experience that the woman who dreamed about the advertising campaign for "life after the bomb" may soon discover new energies and new creative possibilities for action in her life, if only because -- as a result of her work with her dream -- she has begun to call her feelings by their right names, and to reclaim the energies that she was previously wasting in ritualized, repetitive dramas of fear and avoidance in habitual social role relations.

We must all cultivate the courage to call things by their right names collectively as well, even when highly charged community feelings are involved. For instance, when President Reagan recently denounced the truck bombings in Beirut as "cowardly," he was asking us to channel our real feelings of grief and anger into deceptive political forms. Obviously, many derogatory things may legitimately be said of the fanatics who drove the trucks loaded with explosives into the Marine compound and Embassy Annex, but calling them "cowards" is not one of them. It is worth remembering that the last time "peace-keeping forces" occupied American soil, during the War of 1812, U.S. citizens engaged in similar suicidal "heroics,", and we have erected civic monuments to their beloved memory.

We are one, and to indulge in self-deceptive, rhetorical emotionalism about how different we are from our supposed "enemies" is finally only to invite the suicidal self-deception of total technological war, in the repressive effort to resist growth and fuller recognition of the common human condition we share with even our most implacable foes.

Since dreams and working with dreams inevitably puts us more in touch with our self-deceptions, dream work itself offers not only a structural paradigm of the consciousness raising and reconciliation we must accomplish, but also provides one of the best practical methods we have yet discovered for achieving genuine, supportive, growth-promoting, mutually respectful human relationships. My on-going work in hospitals, prisons, and mental institutions suggests that such relationships can be established through dream work, even with and among lunatics, thieves, torturers, and murderers. Simple reflection will demonstrate, I believe, that in a world where weapons of global, suicidal destruction are in the hands of all, the establishment of such relationships offers the only security possible.

We have manufactured the collective nightmare of nuclear war for ourselves in order to scare ourselves into growing and taking the next necessary step in the development of the consciousness of the species. Dream inspiration played a crucial role in the scientific and technological break-throughs which led to our nuclear capabilities in the first place, and the creative energy of dreams may be brought with equal effect to the service of peace and human reconciliation.

In closing, let me offer only one small but vitally important example: Mahatma Gandhi was inspired by a dream to call for the first nation-wide hartal, or religious general strike, in India after the close of World War I. It was effective. In a matter of days the violence decreased dramatically, and the infamous Rowlett Acts were rescinded. Since then, the religiously inspired general strike has become perhaps the single most powerful tool of collective non-violent action we have yet discovered.

The nuclear nightmare is deeply menacing, but it comes to us, like all nightmares, for the purpose of awakening us to what we can become if we accept our true humanity more fully and take the next step toward individual and collective maturity.