"In this model, attempting to remember one's dreams should perhaps not be encouraged, because such remembering may help to retain patterns of thought which are better forgotten. These are the very patterns the organism was attempting to damp down" (Francis Crick & Graeme Mitchison, "The Function of Dream Sleep" Nature 304:111-114. 1983)

Dreamworkers have been responding strongly to Crick & Mitchison's work, and, indeed, it calls for a strong response from us. It denies too much of what we know to be true.

The responses have been diverse because there are so many ways in which those who think like Crick & Mitchison are wrong about dreams and there are so many ways in which they can be shown to be wrong, I wish to address their contentions from the point of view of a novelist who works closely with dreams and dream-like processes.

My approach, then, is fundamentally different from Crick & Mitchison's. They are using sophisticated instruments of research to investigate matters outside of themselves. As a novelist, I am not only the investigator, but I am the thing being investigated, as well as the instrument of investigation. I am not saying this apologetically for when you stop to think of it, no instrument man has yet invented -- and this includes complex computers such as those employed by Crick & Mitchison - is more than a partial expression of what man himself is in his totality. Perhaps it is still true after all this time that "The best study of man is man himself."

You might say that self-awareness is instrumental to sanity. To the extent that we are out of touch with ourselves we dump our toxic wastes in the world around us and get poisoned. We also get all muddled up in concepts that bear no relation to the issue at hand. It is a little insane, after all, for Crick & Mitchison to conclude that the content of dreams is meaningless without examining the content of dreams.

Remembering Dreams

It is also bad logic for them to contend that it is not normal to remember dreams just because most of us do not remember most of our dreams. It is like saying that sex is not an important part of our lives because we do not sleep with the vast majority of the people we run across. Sex is important because of the people we do sleep with, those exceptional ones with whom we can make chemistry. Dreams are important because of the ones we do remember. Our unconscious is not all that stupid and it doesn't constantly require our conscious intervention. As of ten as not the first dream of the night will present a problem that cannot adequately be dealt with. By the time the night's last dream rolls around, the problem has been resolved. We wake up. Our day is a little different. We have changed a little bit in the way we perceive things. Chances are we are not even aware of this. After all, our conscious minds are so small and so preoccupied with a multitude of things that they have neither the time nor the energy to concern themselves with all that goes on behind the scenes.

When something of serious import happens, however, its impact is felt. Like a magnet it draws cathection from many different levels of feeling in us. The resulting dream is remembered and it is powerful. There are three dreams I had like this when I was only five years old. I remember them strongly even today. I have not stopped working with them because these dreams still know more about me than I probably ever will. The important thing about dreams is that some are remembered, spontaneously, by us all, at some time or other in our lives. That Crick & Mitchison's hypothesis fails to account for this is a flaw that runs through their entire work. It is not the only flaw.

A Reverse Learning Mechanism

In essence, Crick & Mitchison employed a very sophisticated computer modelling technique to demonstrate what the great cultures of the East knew thousands of years ago: that there seems to be in our brains a process the opposite of learning which is beneficial to our functioning. There is a famous Zen story about a wordy intellectual full of book knowledge about Zen who visited one of the greatest $Z$ en masters of the day and asked for his teachings. The Zen master talked with the man a bit, saw what was going on in his mind, and then called for some tea. He poured tea into his own cup and then into his visitor's. He kept pouring when the little cup was full. The tea spilled over the brim and spread all over the table and onto the floor.

"But master!" the visitor expostulated, stammering for words, "the cup is already full."

"That is the way your mind is also," the master replied. "If you wish to learn anything new from me you must first make it empty." Here we have Crick & Mitchison's "reverse learning mechanism."

To a much greater extent than we realize, our thoughts flow in pre-established ruts. Zen meditation is a way of making the mind still. The overused circuits become decathected and our thoughts are free to flow in novel patterns that are actually more appropriate to the occasion. Sleep also stills the mind and it also allows novel connections and perceptions to emerge. There is a wisdom in the common solution for a tough problem: "Sleep on it." I am certainly not a very competent writer and I don't consider myself to have a very good imagination. I constantly come across situations in the novel I am writing that are impossible for me to handle. I have learned the hard way not to struggle with my writing. When I come up against a block I simply go into the next room and go to sleep. When I wake up I am not aware that anything has happened. I make a cup of coffee and sit at my typewriter. What appears on the page is beyond me. I don't know where it came from. I couldn't have written it. I simply observe it coming out like someone watching a movie. My mind with its ruts had gotten in the way. When I put my mind to sleep and allow the ruts to extinguish, then the real story can proceed.

Dreams are a very real manifestation of this unlearning mechanism. About six years ago I awoke with a dream that consisted of but a single word: "Calpseunatus." That was the whole dream! How do you work with a dream like that? Well, I used Freud's technique. I free associated. The word itself meant nothing to me so I broke it up into syllables. "Cal" immediately brought to mind California, where I was born. "Pseu" suggested the Latin prefix "pseudo"" meaning "false" like the "pseudobulb" of an orchid which botanically is not a real bulb. "Natus" seemed to me like it might be related to the Latin word for "birth," as in "nativity" or "natal chart." As often happens when I work with dreams, these initial associations themselves sufficed to bring forth a wealth of material. Memories came pouring to consciousness. Often my mother had recounted how the day after I was born she had taken me on a plane from California to New York. Just as often she had told a different story about how while I was still in the hospital in California where I was born, I had developed an infection and had to be kept there a week or so. Working with this dream, I consciously realized for the first time in my life that one of these stories had to be a "Calpseunatus," or a "false birth story" because they couldn't possibly both be true. Again, as often happens in dreamwork, this primary realization brought forth a whole series of realizations about gross discrepancies in the truth as it had been presented to me in my childhood by my mother. It wasn't until years after I worked with this little one-word dream that I first realized my mother was insane. In her later years what she said became too divorced from reality for anyone to pay serious attention to it. My dream saw this early on and showed that the fabric of illusions and lies that she became tangled up in later on in her life had actually begun very many years before and had twisted my own conception of reality, probably from the very beginning.

If there is so much meaning in a dream with only one word, can you imagine what a long complicated and symbolic dream might be trying to tell us. My novel came from such a complicated dream. It has taken me seven years to finally understand what it is about clearly enough to express it.

The Function of Dreaming is to Forget

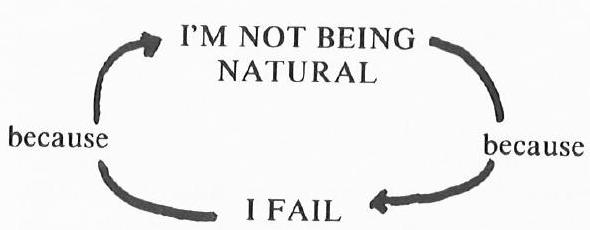

Crick & Mitchison go on to propose that the function of dreaming is to forget. Here they make a brilliant cognitive leap into a realization that has been common knowledge to psychologists since the time of Freud. But unfortunately this impressive leap lands them squarely on their heads for they presuppose it is dreams that need to be forgotten when in fact it is our waking mentation - the established ruts of thinking and perceiving our minds have fallen into as a result of learning and experience - that needs to be forgotten before the mind can adequately respond to experience that is entirely novel, different than anything encountered before; in other words -before the mind can learn. So much of our perception itself is a product of what we know to expect that we often do not even consciously take in the completely new data when it presents itself to us. Our conscious mind, like the talkative intellectual in the Zen story, has a full cup of tea. The new data, especially if it doesn't fit our preconceptions, spills right out.

My experience has been, however, that the unconscious mind does not miss a cue. It soaks up an extraordinary amount of the spilled-out impressions and holds them indefinitely. Furthermore, it is active and capable of rearranging this data. It does this actively and yet it is a passive process in the sense that we are entirely unaware of it on a conscious level. Dreamwork, like Zen Buddhism, is based upon the knowledge that it is our waking mentation most of all that needs to be forgotten. Crick & Mitchison's model flies in the face of thousands of years of human experience and it flies in the face of the facts they themselves could have discovered had they worked with the content of their own dreams instead of with a sophisticated computer model. I could give volumes of detailed documentation from my dreams and journals over the past decade to illustrate this point and I know many of you could do the same. I shall limit myself to two:

(1) Dreams of my Marriage

A number of years ago I was married. I believed in the sacredness of marriage. I believed that love goes through bad times and it is important to stick it out, to grow together, to weather the difficulties. I loved my wife very much. My dreams told me that this relationship was over. They told me that the essence of the whole bond had been violated too severely for it to continue. I didn't want to know this so I didn't know it. I continued believing what I needed to believe to keep things the way I needed them to be. My dreams were busy at work. Like a masterful lawyer they organized the facts of the case in such a way that it was increasingly difficult for me to deny the truth of the matter. I was incalcitrant, I was persistent, I was essentially blind to the facts. I didn't listen to my dreams. I worked with them all this while but it was only when the marriage finally broke up in the most painful and destructive way for me that I could finally admit the truth to myself. My dreams knew all along. It was my waking presuppositions that needed to be forgotten, not my dreams. The "parasitic modes" are not dreams like Crick & Mitchison think. They are our waking ideas.

(2) Dreams of my Father

I hated my father. I saw him as a horrible and unfeeling man who wrought a great deal of pain and suffering on me and my mother. I ran away from his home and for sixteen years remained estranged from him and completely out of communication with him. A few years back I became aware that I was having quite a few recurring dreams of returning to see my father. It was always unpleasant and even in the dreams I always sought to avoid him, but the dreams always took me back to him, again and again and again. I did a Calvin Hall dream series analysis of this whole entire sequence of dreams as if they were different pieces of one huge jig-saw puzzle. I discovered I loved my father. I discovered he was the single most important person in my life. I couldn't quite understand how all this could be. In this case I heeded the dreams. I travelled to the distant city where he lived. The instant we met, something happened that is difficult to describe. A weight of decades was lifted from me. I literally had the feeling I was walking two feet off the ground. He and I spent many powerful and intimate moments together during the ensuing week. I had found a soul mate. I made plans to return for Christmas. For the first time in 16 years I had a home, I had someone to spend a holiday with. A week after I returned to New York, my brother phoned that my father had suddenly died.

My waking mind never would have gone back to see him in time, never. I would have had to live out the tragedy like I did in the marriage. In this case it is rather clear that my dreams knew much that I didn't. Dreams are hardly parasitic modes of thought as Crick & Mitchison maintain. Quite the contrary is true. Subsequent investigations that I carried out made it quite clear to me that what had been parasitic upon me were the lies that my mother had fed me about my father since as early as I can remember. My cup was full of those lies. There wasn't any room for the truth. It spilled into my unconscious, little bits and fragments of data from here and there, and organized itself into the meaningful dreams. The function of dreams is to teach the waking mind how to forget what it thinks it knows but doesn't.