A myth can be described in many ways but the metaphor of a "chaotic attractor" is especially suitable. In chaos theory, there are several types of "attractors" but a "chaotic attractor" finds order in what appears to be incomprehensible data by helping us to discern an underlying pattern. In much the same way, a myth can organize a constellation of beliefs, images, emotions, motives, and values that can, in turn, bring order and direction to a society, an institution, a family, a person, or to an entire culture. From a psychological perspective, a myth is an imaginative narrative (usually expressed in words but sometimes expressed in dance, images, etc.) that addresses existential human concerns, and that has behavioral consequences. Myths are more imaginative (more accurately, "imaginal") than empirical, and this is where a mythic narrative differs from an empirical scientific narrative. Empirical science, despite its successes in explaining the workings of natural phenomena, is virtually incapable of fulfilling the other functions that myth has provided over . the millennia - assisting the passage of individuals through the life cycle with rituals and ceremonies (e.g. ways in which myths are "performed"), identifying a person's place in the social world of work, love, and play, as well as helping him or her to link with the world of spirit, of the "ground of being," or of ultimate value.

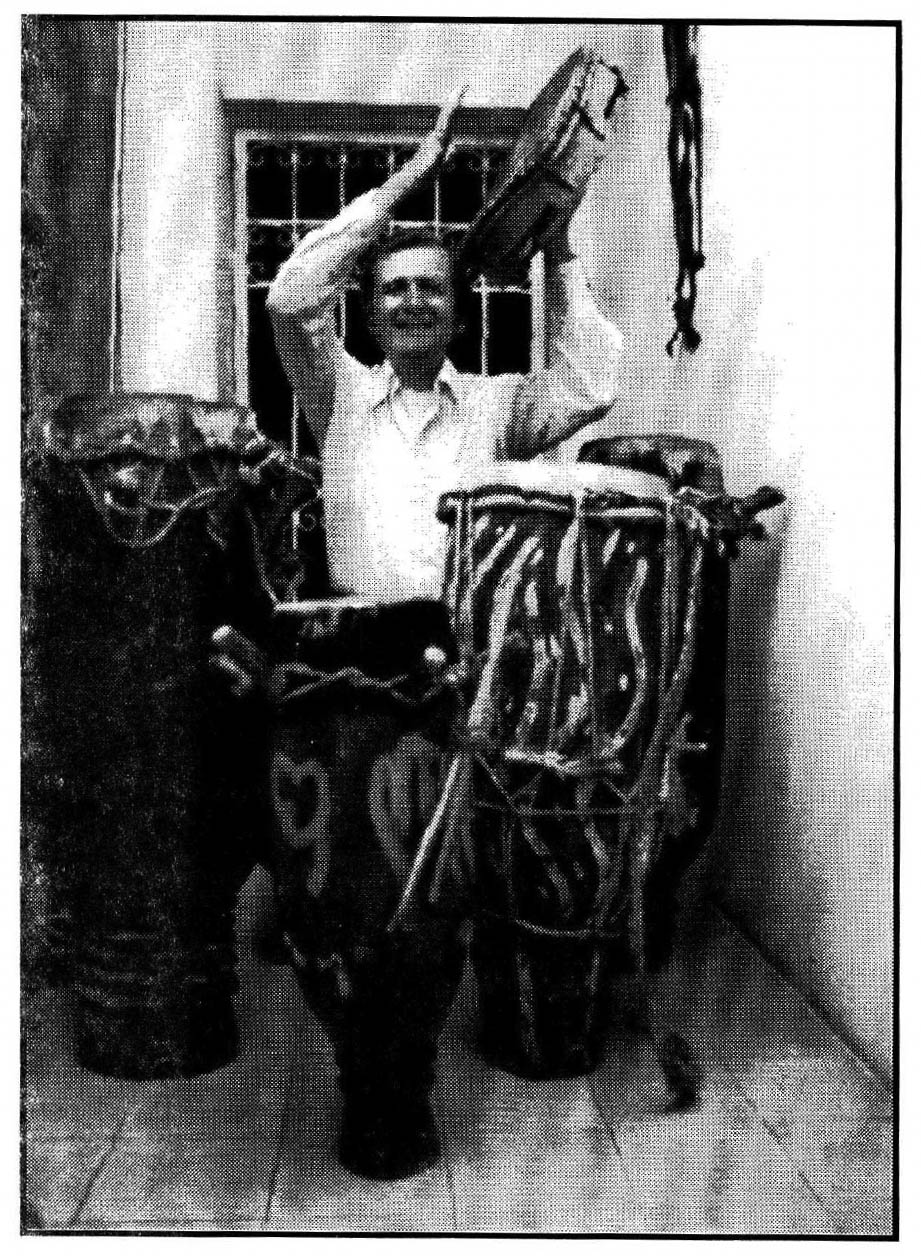

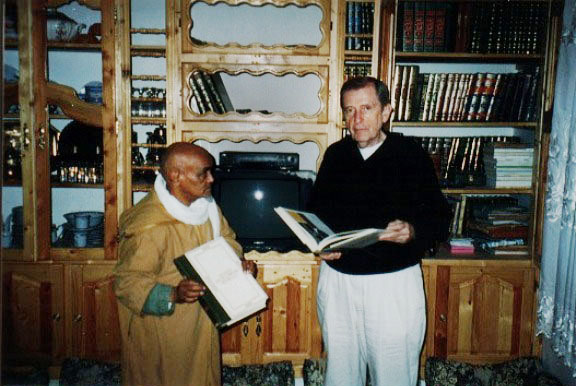

This essay will use these perspectives on myth (one covert, one overt) to present, for the first time, a particular transcription of a portion of oral mythology. We were honored to be allowed to record these stories during a trip to Salvador, Bahia, Brazil in 1997 where Cau Trigo, a young Brazilian man working with the Kariri Xuco tribe introduced us to Tinze, the "Nhenti" or "Keeper of the Traditions."

The History of the Tribe

The Kariri Xuco' are a coastal tribe in the Brazilian northeast (Novaes da Mota, 1987). In the 13th and 14th centuries, the warriors of the Tupi tribe pushed the Kariri Xuco' from most of their coastal land into the interior. They now live along the west side of the San Francisco River, the second largest in Brazil, after the Amazon, with which it does not connect. Hydroelectric projects interfere with the tribe's water supply, badly needed for fishing and irrigation. Only 10% of the land they presently occupy is now legally owned by the tribe itself, the remaining property being subject to state and federal regulation and utilization.

This process of losing control of the land and, therefore, their destiny, began during the days of colonization. The Portuguese made slaves of the Tupi Indians, and the European historians called them the first people of the coast, not knowing that the Tupi had supplanted the Kariri Xuco' before the Portuguese arrived. It took a century for the Portuguese to locate the Kariri Xuco'. With the advent of colonization, the federation of northeast Indian groups disintegrated. The Kariri Xuco', whose culture had not recovered from their ejection from a coastal area to a dryer river area, were further destabilized by the Portuguese.

There were bloody skirmishes between the Indians and the colonizers. Hoping to reduce expenditures on war, the Portuguese brought Capuchin priests from France as well as Jesuit missionaries in an attempt to pacify the region. This plan succeeded but resulted in the loss of much of the Kariri Xuco' culture.

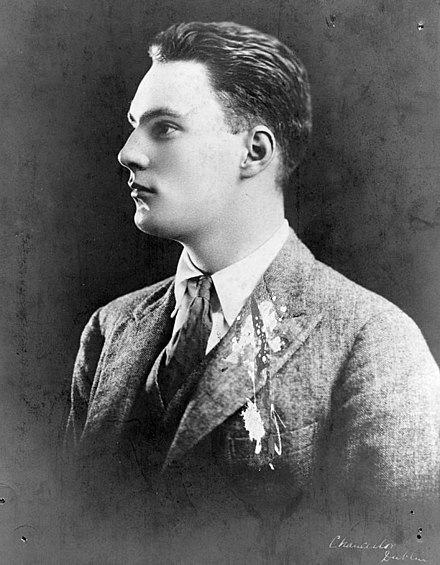

Personal History of Tinze

Tinze told us that he had always had an interest in the myths of his tribe. But when a child attempts to listen to the tales told by tribal elders, the custom is to tell the child to go away. Only a child with determination will respond by saying that he or she wants to stay and listen. Tinze was one of these children. In addition, he often pretended to be asleep while the elders were telling stories. He still remembers the state of consciousness he fell into during those hours- a mixture of relaxation induced by having his eyes closed, alertness needed to hear the stories, and fear of being discovered.

Over the years, Tinze gradually won the confidence of his elders. Little by little, he was given tasks and responsibilities. As he was successful in each of his missions, he gained more access to the stories along with new responsibilities.

In his early 30s at the time of our interview, Tinze told us, "From the time I was a child, I have been interested in tribal stories, and eventually I committed myself to the recovery of the Kariri Xuco' culture. I could see how a revival of these stories could stop the loss of our culture. Once I had attained sufficient wisdom, the elders listened to my ideas to reconnect members of our tribe with the spirits, with nature, and with each other." Now Tinze is the tribe's "Nheneti" or "Keeper of Traditions." This position involves secretarial work, representing the tribe to the outside world, communicating with tribal counselors and heads of families, as well as with the tribe's chief and shaman.

Tinze told us that such responsibilities are not common for a person as young as he is, but that the tribal leaders admired his devotion to the ways of the ancestors and his skill in harmonizing and mediating conflict within the tribe. Shortly before our interview, Tinze was honored to receive a secondhand typewriter for use in his official duties.

Presentation of Myths

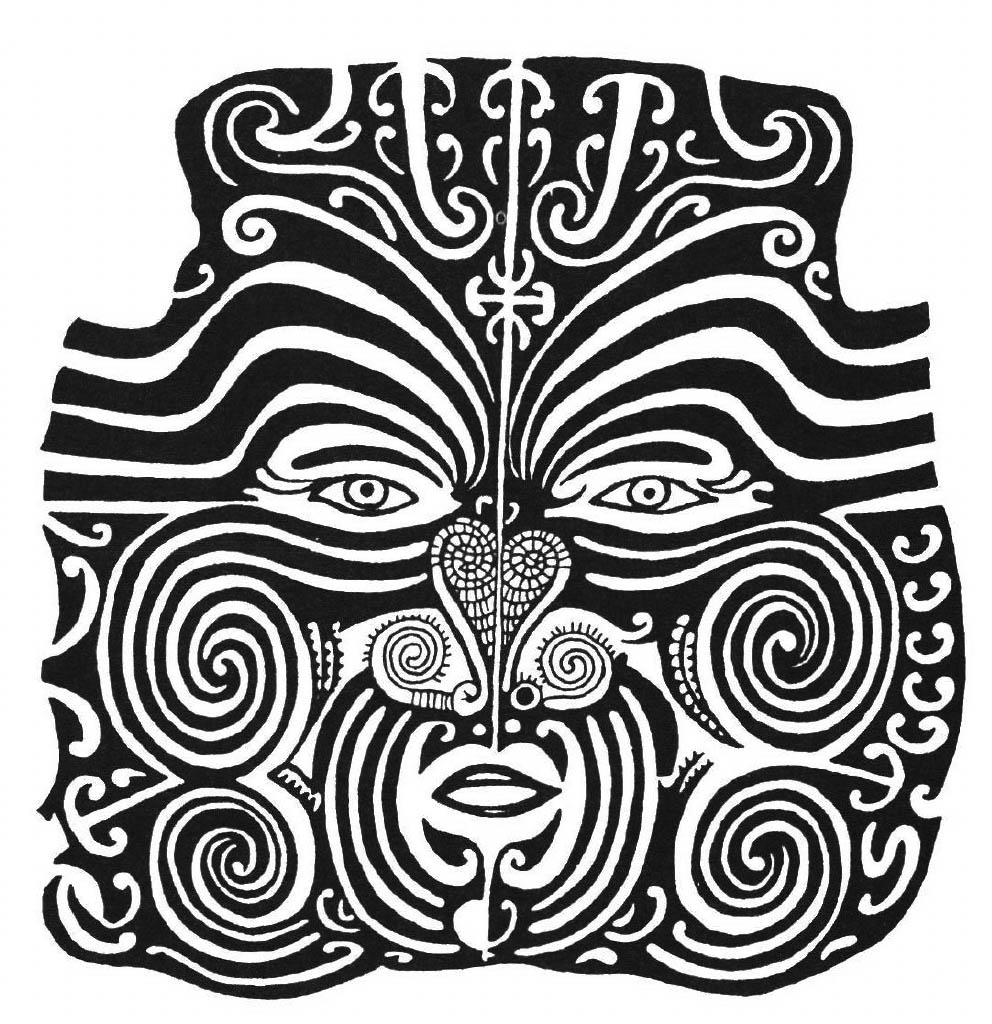

The Kariri Xuco' believe that each river contains several "Maes do Rio" or "mothers of the river." These spirits live in the river and must be respected because of their power. Dedzu's is one of these spirits and resides in a portion of the Rio San Francisco -the San Francisco River- which originates in the state of Minais Gerais, eventually flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. Kariri Xuco' fishermen try to win favor from Dedzu's because if she likes them, they will always bring home fish, and their catch will surpass that of others who have not won her affections. Indeed, some fishermen give Dedzu's so many presents - delicious foods, beautiful flowers, perfumed herbs - that their wives become jealous and see Dedzu's as a rival. But if a fisherman does not abide by Dedzu's wishes, he will catch fewer fish. And if he ignores or insults her, he is at risk for having his soul stolen. Dedzu's domain is filled with stolen souls who work as slaves to do her bidding, including going on expeditions to steal other souls. The loss of one's soul is a terrible tragedy, far worse than losing one's life.

Dedzu's is a spirit of the night. At midnight, she comes out of the water and visits the riverbank, where she eats the corn and beans left for her as well as putting the gifts of flowers in her hair and the perfumed herbs on her body. When surprised by a human being, she jumps back into the river and the intruder might hear a splash of water.

Dedzu's powers are activated by the disappearance of the sun's rays. On occasion she will allow herself to be seen by one of the fishermen she favors. Her body is beautiful but translucent; she is human in form but has gills on her neck. She wears no clothes but her long hair flows over her body. These fishermen can stroke her body and engage in intimate conversation with her, but like other Kariri Xuco' spirits, she does not engage in sexual activity with humans. She is capable of having children, however, her pregnancy sometimes being evoked by the intimacy she shares with one of the fishermen. She can become very jealous of other "Maes do Rio" and envious of the wives and girlfriends of her favored fishermen.

When Tinze was in his early 20s, he was accustomed to returning home with a fine catch of fish, frequently bringing back more than the other fishermen. Still, he followed the advice of his mother, who told him, "When you are fishing, be careful to avoid the river spirits. Take care not to fish too much in one place or the River Mother may entrap you." Tinze's mother suspected something of which he was unaware: the River Mother was preparing him for an intimate relationship.

In the meantime, Tinze began to have girlfriends and the Water Mother grew jealous. For the first time, Tinze returned to the village at the end of the day without any fish. He tired easily and spent much of his time sleeping. His friends thought that he was ill, but his mother suspected that the River Mother was trying to steal his soul. Indeed, this suspicion was confirmed in the dreams that Tinze's mother had at night about the River Mother, who accused her of being overly protective of Tinze. One way in which Tinze's mother protected him was to put a small piece of tobacco over the door of the house and also in his shorts, because this sacred plant has the power to neutralize malevolent activities of the water spirits, and of other invisible forces as well. Tobacco represents the benevolent spirits who can protect human beings from invisible forces that are negative, especially those that result in soul loss. Tinze's mother was successful and her son recovered from his weakened condition.

Another group of water spirits are the "Pretus do Rio," or the "Dark Ones of the River." One of the most powerful is Irotzu, another spirit of the night. Often, he stands at the river bank observing the fishermen. When a fisherman least expects it, Irotzu dives into the water; a splash is heard but nothing is seen. Yet the fishermen know that Irotzu is nearby and monitors their work carefully. They know that Irotzu will punish them if they fish during the time when fish eggs are hatching. They know that they must fish only when necessary, and must use only natural methods of fishing. For example, some men toss small bombs into the river and collect the fish that float to the surface. They are subject to the wrath of Irotzu, and if they try to protect themselves with tobacco, Irotzu will go after one of their immediate family members.

Women of the Kariri Xuco' tribe can fish as well as men. One of Tinze's cousins had been fishing for a long time with no success. Finally, in frustration, she called out to the river spirits, "Stop joking and give me some fish." Such a statement was disrespectful, of course. She immediately felt dizzy and almost fell out of the boat. Her sister caught her and rowed back to shore. Eventually, the transgressing woman regained consciousness, but her eyes burned badly. Her brother told her that her head looked as if it had been hit by a bow."

A healing session was initiated, which successfully aided the woman's recovery. The Healing God's full name is sacred and can never be mentioned in public. However, there are many healing spirits to whom prayers can be offered directly.

The religion of the Kariri Xuco' is syncretic. Since the time of the missionaries, members of the tribe have entered into relationships with Christian Saints through their prayers and public rituals. As Tinze remarked, "We love Jesus Christ and admire Mother Mary, but we retain our ancestors' religion as well."

A third water spirit is "Cabe a Grande" or "Big Head," a name applied collectively to a group of invisible children who play in the river. These spirits have heads that are disproportionate in size to the rest of their bodies. Their antics can be observed when there is a rush of white water, a sudden eddy, or an unexpected phenomenon. Tinze told us, "One day I saw a stream of water flowing against the current and knew that Big Head was being playful."

These spirit children do not interfere with human affairs. However, fishermen must be aware of their behavior or their boats might get caught in the rapids that develop when Big Head is making sport.

Placing of Myths Within Our Perspective

The narratives provided by Tinze illustrate our descriptive model of myths. On an overt level, these stories are imaginative narratives that address such important human issues as family relationships, food supply, and matters of health and safety. The narratives impact behavior, giving instructions as to how fishing must be done, how the spirits must be pacified, how souls must be protected, and how sickness must be treated.

On a covert level, these myths can be said to "attract" beliefs (tobacco will protect someone from malevolent spirit activity), emotions (parental concern for the souls of their children), images (the description of the Water Mother with her gifts and long hair), motivation (bringing home a fine catch of fish is so important that one is motivated to respect the water spirits), and values (the loss of one's soul is the ultimate disaster).

The utility of our descriptive model can be demonstrated with the myths of the Kariri Xuco'. But it can also identify mythic elements in other imaginal narratives. Fairy tales are told for entertainment, but often include moral lessons. Legends tell of semi-historical feats of heroism but frequently refer to a culture's values. Sagas are compilations of legendary accounts but the motives of their characters are frequently clear.

Even so, imaginal narratives that deal with superficial issues and do not contain behavioral implications lack the qualities that would qualify them as myths. In a world where chaos seems to be on the increase, the underlying attractor provided by myths can provide a sense of order to individuals as well as institutions, families as well as societies, and perhaps even to cultural revivals as we observed in Tinze' s accounts of the Kariri Xuco'.