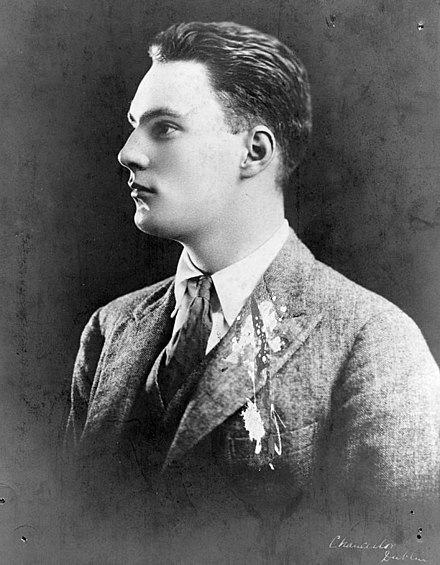

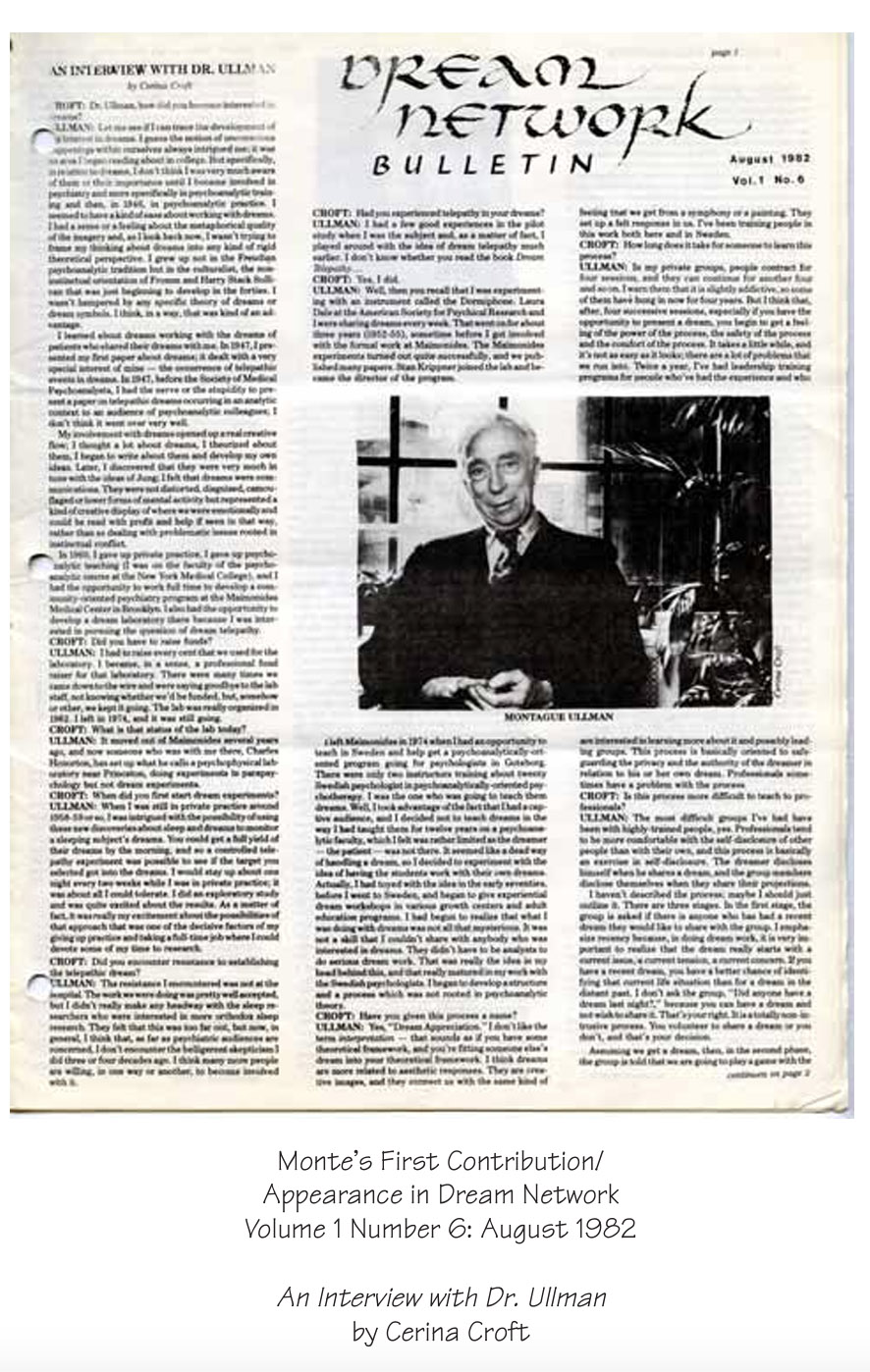

In 1964 I accepted Montague Ullman’s invitation to direct the Dream Laboratory at the Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York. I had met Monte at various conventions of the Parapsychological Association, and had told him about my lifelong interest in dreams and anomalous phenomena. At Maimonides, the basic research procedure developed by Monte was to fasten electrodes on to the head of a research participant, and then take her or him to a specially designed soundproof room where the electrodes were plugged into a receptacle. In the meantime, a staff member would throw dice, add up the total, and go to a stack of envelopes, each of which contained a vividly colored art print. The envelope was given to another staff member who would take it to a distant room, open it, and spend much of the night attempting to “transmit” the images to the sleeping research participant.

The participant knew that the task was to incorporate these images into her or his dreams, and would be awakened and queried whenever the electroencephalograph tracings indicated that dreaming was probably taking place. In the morning, the participant would be interviewed regarding associations to her or his tape-recorded dream reports. The final step was for the participant to inspect copies of all the art prints in the “pool", ranking them in terms of their similarity to the recalled dreams. Over the course of the decade that we worked together, we amassed data indicating that some sort of anomalous ”transmission” and “reception” had taken place at statistically significant levels. Together, we wrote dozens of research articles and a popular book on this investigation.

Monte held regular staff meetings with me, other team members, and the many student volunteers who joined us over the years. His creativity and enthusiasm was quite apparent during these meetings, and we all worked collaboratively to find ways to implement his ideas. As a psychoanalyst, Monte had a repertoire of so-called "telepathic" and "precognitive" dreams concerning his clients, and bringing these experiences into a laboratory setting will be known someday as a major contribution to psychological science. Monte and I traveled to Germany, Belgium, and France for various conferences, where his wit and keen observations delighted all of those who were in his company. Eventually, he revolutionized psychotherapy in Sweden with his series of dream seminars, and I was regaled with marvelous stories about Monte's visits during my own workshops in that country.

Monte was a longtime friend of David Bohm, the quantum physicist, and often related our work to Bohm's notion of "holomovement," a subtle, underlying, interpenetrating component of the universe that he described as an "implicit order." This "implicit order" represented the dynamic expression of the interconnectedness of the universe, and this "order" could involve an inherent awareness that might be the foundation for anomalous events such as the anomalous dreams we studied in our laboratory at Maimonides. Monte has described how, in the interest of fostering connections with other people and the natural environment, dreams are often confronted with parts of their lives that are "disconnected." The honest part of a dream's confrontation contains a potential for positive change. Therefore, we felt that our studies of anomalous dreams had practical implications, not only for psychotherapists who try to help their clients connect the torn patterns of their lives, but for everyone who seeks ways to to affirm their liaisons with other people, with nature, and with whatever they consider their spiritual groundings.

Once the Maimonides laboratory ran out of funding, Monte and I continued our "dream relationship." I attended one of his celebrated leadership training weekends, and urged my students at Saybrook Graduate School to trek to Ardsley, New York, for a similar experience. The unanimous feedback was that the weekend was unforgettable, transformational, and that they would be able to use what they learned to appreciate their own dreams as well as those of their clients or friends. Monte is too modest to admit it, but—more than anyone else—he pioneered what has been known as the "grassroots dream movement," an interest in dreams that has spawned the International Association for the Study of Dreams, as well as "leaderless" dream groups all around the world. These groups follow the procedures outlined in Monte's weekend seminars as well as his books on the topic.

I was more fortunate than the recent participants in these seminars, because I was able to enjoy not only Montes' company but that of his beloved wife, Janet. She and I had many interests in common, including contemporary art, "al fresco" dining, and our opposition to the involvement of the United States in the civil war raging in southern Vietnam. Janet and Monte made a lively (and lovely) team, and the vibrancy of their relationship was a wonder to behold. Monte and I still collaborate together on subjects of mutual interest and, when we do, I have the sense that—in some way—Janet is still with us.